| Temple talk for Sunday

|

||||

|

Temple talk for Sunday ( Photos were taken and added by Ai-Lin)

Welcome to the QVMAG Guan Di Temple. (by Burcu Keane)

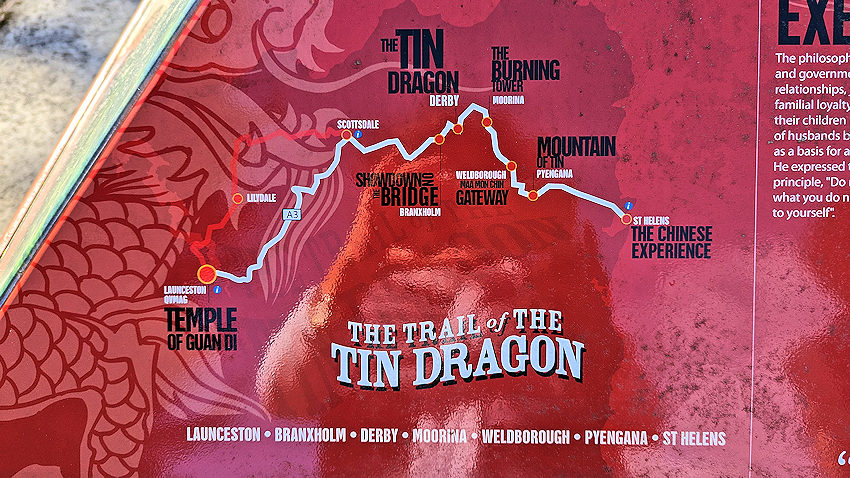

This is actually not one temple, but the contents of six temples from Tasmania’s north east: Lefroy, Branxholm, Moorina, Gladstone, Garibaldi and Weldborough.

These were built mostly in the 1880s by Chinese miners who came to Tasmania to mine tin.

|

||||

|

||||

|

- Burcu Keane giving a presentation of the history of the Temple -

They had their heyday during this time, but gradually, as tin mining became less of an economic proposition, the smaller temples closed, passing on their contents to the larger temple at Weldborough. Eventually, in 1934, the last temple custodian, Jee Harm, decided to return to China. He arranged, with the help of influential Chinese leaders in the community – notable among them was James Chung Gon - to move the temple contents to Launceston, where the bulk of Chinese people now lived. The temple was given to the people of Launceston, and a special room – this one – was built on the side of the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery to serve as the new temple. The temple remained a functioning temple, and is still one to this day.

The reproduction banner above the display case in the corridor is actually the donation document for the temple. It reads: To the people of Launceston, from the residents of Tin Mountain. The original is too delicate for long-term display.

Chinese people actually have a long history in Tasmania. The first reference we have been able to find was to 9 Chinese carpenters who were brought to the colony in 1830 to make furniture. However it is highly likely that more Chinese people had already come as part of the crews of the various ships that visited the colony.

The biggest influx, however came from around 1870. The Gold Rush on the Australian mainland was now in full swing. With the discovery, first of gold and then of tin in Tasmania, many miners came to try their luck in Tasmania. The Lefroy goldfields were the first to attract miners, but it soon became evident that the real money here was in Tin, not gold.

Luckily, the techniques for mining tin are almost identical to those for mining gold. The majority of this mining was Alluvial mining – using water to separate out the small pieces of tin from mud, by sluicing. The tin is heavier than the surrounding substrate, so as sand and clay are washed away, the tin remains in the sluice.

Alluvial mining has the advantage of requiring very little technology, and so is suitable for those wishing to work small claims.

Conditions on the tin fields in Tasmania’s north east were very harsh. The country is usually wet, hills and mountains steep, and it is very hard to transport ore out and supplies in. Because of this, Chinese miners became quite successful in Tasmania. Rather than operating completely independently, the communities would support each other, allowing them to mine more marginal areas. This also gave them a reputation as hard workers, meaning that the degree of racism encountered on the Mainland goldfields was less severe here (although still present).

Many miners came to Tasmania using what is known as the Credit Ticket system. A wealthy or successful businessman and community leader would sponsor miners from their home village or area to come and work here by paying their passage and entrance taxes. These would then be paid back over time as the miner earned money by mining.

Almost all Chinese miners came from one area in China – Guangdong Province, in southern China. At the time, China was suffering from a period of economic depression, and work was hard to come by, particularly for the rural poor. Many miners came to Australia in order to make money, and send most of it back to China for their families. For this reason almost all of the miners who came here were men.

James Chung Gon was unusual in this respect. Although he came out to mine, as did so many of his contemporaries, his success came first through selling his share of a mining lease, but mostly due to his skill in both agriculture and business. He is one of the few Chinese immigrants at the time to have married in China and to have brought his wife back to Tasmania. This places him with Maa Mon Chinn and Chin Kaw as the only men to have raised families in Tasmania without a European woman on one side of the partnership.

As the Chinese miners working in the North East were far from all things familiar, they needed some sort of social glue to hold them all together. All miners spoke dialects of Cantonese, with many speaking the Tsi Yup language, but even though all were from Guangdong Province, not everyone spoke the same dialect. Sharing a religion could bring people together, and temples were centres for the community.

All temples in Australia during this period were dedicated to Guan Di as their principal deity. Guan Di was originally a real person – he was a General during the Three Kingdoms period of Chinese history, who over time had ascended the Buddhist pantheon to become a deity of ‘Emperor’ rank. The portrait in the shrine on the altar at the back of the temple shows Guan Di with his son and his principal military leader and bodyguard.

However Guan Di’s main attraction as a deity for overseas Chinese is his position as a patron of Brotherhood. The concept of Brotherhood – especially sworn brotherhood between unrelated people - was central for a group of people with a different culture, far away from their homes. Guan Di also represented the power to prevent war and cast out demons, as well as wisdom and learning.

Guan Di is usually depicted in Buddhist iconography with a red face. However the portrait in this temple shows him in Taoist representation, as the temple does not represent a pure Buddhist form of worship, but is more of a hybrid of Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian philosophies.

The red plaque on the wall on the right hand side of the temple reads Guan Di Miao, which means Guan Di Temple, and originally hung at the entrance of the Weldborough Temple.

The large weapon in the corner is a Guan Dao, or the ‘big knife’ of Guan Di, and represents Guan Di’s military prowess.

The rocking horse is a fascinating item – it represents the famous horse of Guan Di, called the Red Hare. This is a great piece of local adaption. It is a European-style rocking horse, but covered with pigskin and horse hair, and fitted with a Chinese-style saddle for use in its new religious function.

The temple contains other items of local manufacture as well – the gong in the right-hand corner is one of these. The gong itself is made in China, but the frame that holds it is constructed from a ‘Westwood’ type bicycle wheel rim, and is held up with re-purposed telephone cord.

However the bulk of the items in the temple were made in China, by specific temple craftspeople, and they represent a huge monetary investment. Bear in mind that many of these were placed in tiny wooden and corrugated-iron buildings in the bush. The large plaque of a golden palace, or scene from heaven is hand-carved, covered with gilt, and originally backed with tiny mirrors. This most likely used to hang in the tiny Branxholm temple, which is depicted in a photo on the outside wall of the temple.

In the case in the corridor, we have put some items relating to the Chung Gon family on display, and ShuHan will show you some of the costume items collected by Ann Chung Gon on her trip to China later on.

These items show both the degree to which the Chung Gon family became an integrated and key part of northern Tasmanian society, and also the degree to which they remained deeply connected to their Chinese heritage.

The abacus was used in their Greengrocer’s shop on Brisbane street. The two promotional calendars show how the shop served the entire community, not just the Chinese community. They depict non-Chinese topics.

(Calendars - left: features an illustration of a typical English country cottage. 1932. - right: features a portrait of the popular actress Joan Crawford. 1936)

The trinket box and tea caddy were sold either in the family’s Canton gift shop in Launceston or in the Peking gift shop in Hobart. They were both made in China, and imported for sale by the family. The fact that the Chung Gons were having items made in China shows that their links to their country of origin remained strong, despite the family eventually making the decision not to return to China.

Finally, the photograph of Mei (Mary) Chung Gon and Edward (Teddy) is interesting, as it shows both family members in Chinese costume, and if you look at Mei’s feet, you can see that her feet are tiny. She, as a member of a high-class Chinese family, had bound feet. She was one of only two Chinese women in Tasmania to have bound feet, and her shoes are in the Museum’s collection – you will see some of them (or will have seen some of them) in ShuHan’s presentation.

|

||||

|

|

||||

| I would like to invite you to light some incense in the temple to pay respects to your family’s ancestors, should you wish. | ||||

| ______________________________________________________

|

||||

|

Dear Mia and Bob and everyone who joined the Chung-Gon family reunion at QVMAG on Sunday the 16th of April,

Thank you again for visiting us and sharing with us the wonderful stories associated with Chung-Gon family and Chinese community in Tasmania.

I have attached here the script of my Guan Di Temple talk. It was originally prepared by our Senior Curator Jon Addison who unfortunately could not join us on the day due to a family bereavement.

Jon Addison

As always, we would love to hear your thoughts and comments and look forward to catching up with you again on your next visit.

We would love to hear more about the feature article on the Chung-Gon family 150 year reunion with ABC Hobart.

Please do not hesitate to get in touch with ShuHan and myself should you have any further questions.

Kindest regards,

BURCU KEANE

|

||||